Domain Knowledge: The Machine Learning Unlock

We know data science is hard enough when working with metrics. Customer churn, ad clicks, cart abandons. Even the stuff collected internally is patchy with data quality leaving a lot to be desired. But they’re numbers. They behave. To a certain extent.

You know what doesn’t? People. Particularly when the pesky emotions of love are involved. You can’t turn ‘chemistry’ into a float value.

I tried to build a linear regression model to predict romance thinking it would be a fun Valentine’s experiment and an interesting feature engineering challenge. Instead I found inconsistencies, bias and impossible variables. Today we’re going to learn just how important domain knowledge is to data science. Welcome to my data science nightmare.

When the Data Doesn’t Exist….

As a data scientist, I’m pretty sure I have the skills to tackle this project but I have one big challenge standing in my way. I don’t work for hinge, or match.com, or insert your favourite modern day dating platform here. That means I don’t have access to big swathes of data of real singletons looking for love.

But to train a supervised model, I need labels. I need a dataset where the ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of a relationship is a known fact. So instead of mining the love lives of everyone I know, I’m using something we all obsess over anyway: TV characters, their relationships and the messy love stories we know by heart.

Now that I’ve got the idea, I needed an actual plan.

If only building a TV character dataset were as easy as clicking through Create-a-Sim

Assembling the Relationship Dataset

First, I had to build a dataset where every character has the basics: height, hair and eye colour, the actor who plays them, the TV show they’re from, and their personality type. Then I needed the relationship side: who they dated, and what the relationship status was.

And honestly it wouldn’t it be amazing if a dataset like that already existed on Kaggle?

Yeah. We can dream.

In reality, this kind of data doesn’t come neatly packaged. It’s messy, incomplete, and spread across different sources. So I had to break the problem into smaller chunks and build it piece by piece.

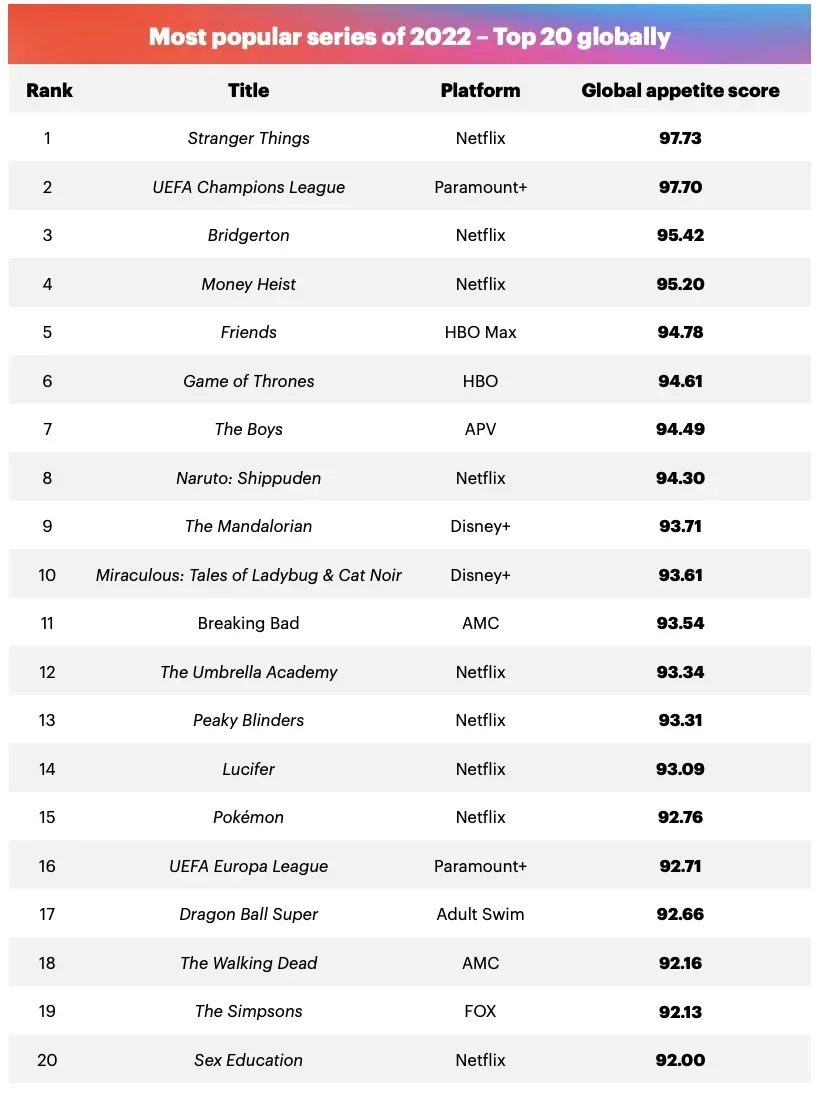

To keep it manageable, me and my team picked around 50 TV shows that we know and love, plus a few that are just too iconic to ignore. Like I had to include Game of Thrones, the relationship dynamics are literally unhinged.

And if I missed your favourite show, tell us in our Discord and I’ll add it to the list.

Familiar shows, smarter data: knowing the world behind the numbers.

We also limited it to about 50 TV shows we actually know on purpose and that wasn’t just to make scraping easier. It was because domain knowledge is basically a cheat code in data science. When you understand the world behind the data, you can spot what’s a real outlier versus what’s just an error.

For example, if I pull character heights from Game of Thrones, the minimum height in the dataset is going to look wildly low. If you didn’t know the show, you might think, “That has to be a bug.”

But if you do know the show, you immediately realise: that’s not a data issue and it’s because one of the characters is played by Peter Dinklage. The outlier is real, and it actually makes the dataset more accurate.

So choosing shows we know wasn’t biased and it was quality control.

Fans as data scientists: turning fictional characters into MBTI case studies.

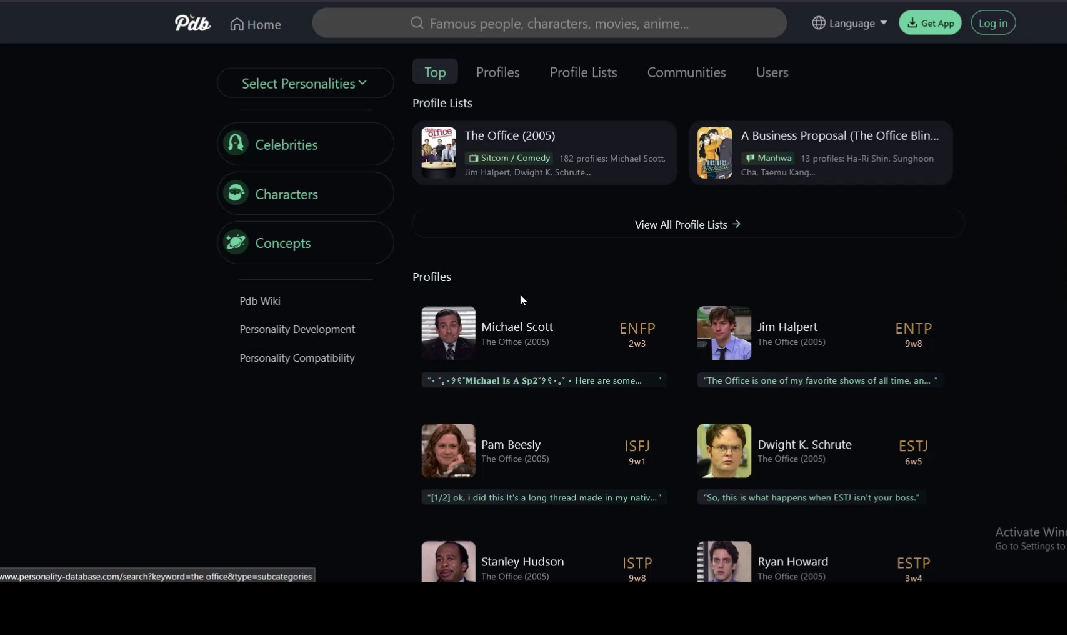

From TMDB to MBTI

First, I pulled the basics from The Movie Database (TMDB): the show, the characters, the actors, and gender. Nice, clean, structured and the kind of data that gives you false confidence.

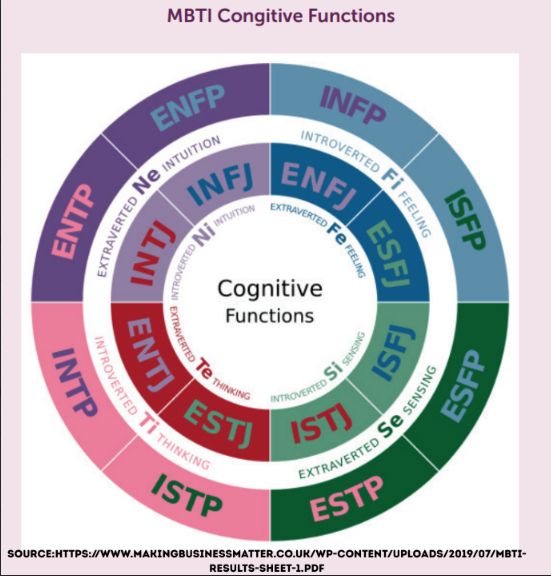

Then I needed personality types. I went to a fan-voted personality database, where fans basically treat fictional characters like real case studies and vote on their Myers–Briggs type. And by the way, if you didn't know Myers-Briggs (MBTI) is a personality framework that groups people into 16 types using four letter pairs: E/I (introvert vs extrovert), S/N (facts vs patterns), T/F (logic vs values), and J/P (structure vs flexibility).And honestly? If anyone has the ultimate domain knowledge here, it’s the fanbase . These people know the characters better than the writers.

And the funniest part: the most common personality type in the whole dataset was ESFP(Extraverted, Sensing, Feeling, Perceiving) also called “The Entertainer.”. We can all agree Joey from Friends is basically the mascot for that type.

Mapping Personalities using the MBTI system

Enhance… Enhance… Nope.

For hair colour and eye colour, I had to go hunting through images because there’s no proper database that just hands you “character eye colour” in a clean column. And this is exactly why domain knowledge matters: actors don’t always look like their characters. They dye their hair, wear contacts, and sit in makeup for hours. Sometimes they end up as an actual alien in Star Trek. So if I’d pulled the actor’s real features from a random bio page (which doesn't exist by the way, I tried.), I’d be training my model on the wrong face.

I had to do some funky machine learning to get this right and if you want a follow-up video on exactly how I did it, then you will have to let me know via our discord

Also, quick limitation: this works way better for hair than eyes. Hair is usually big, obvious, and consistent across scenes but eyes are tiny in most screenshots. Half the time the face is low-res, the iris is basically a handful of pixels, and then you’ve got lighting, colour grading, and filters on top. So eye colour quickly turns into “enhance… enhance… nope.”

And finally, for height because no one just has a “character height” column lying around. I used CelebHeights to estimate character height based on the actor.

That part got messy fast because I made a mistake by matching characters instead of actor names. Some actor names didn’t line up, and a few merges failed, so I had to re-run parts of the pipeline to fix the errors.

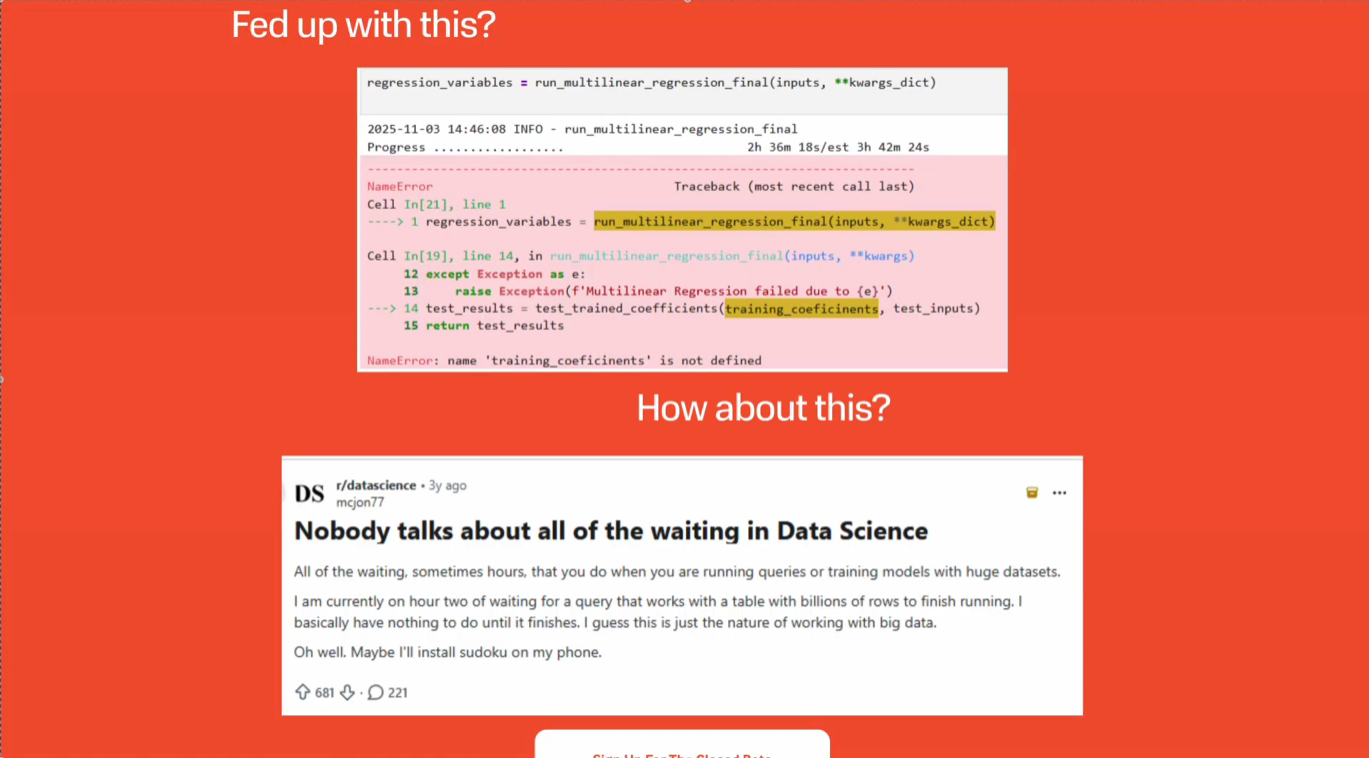

And by the way, how I wish I had the Evil Work’s PUFF platform for this because it significantly cuts down rerun time by only rerunning the parts that changed but the tool has literally only become available in the last couple of days. We’re going to have a closed beta so you can use it next month, you can find out more by clicking this link

Showing just what Evil Works Puff platform can do

Love, Lies, and Labels

Now the most difficult and honestly the most crucial part of this whole project was getting the relationships for each TV show. I wish there was a clean, magical dataset that just lists every couple, who dated who, who married who but no. Of course not.

At first, I tried doing it the hard way: digging through fan wikis and forum pages show by show. And that was easily the most painful part of the entire pipeline.

Then I had what felt like a genius idea: I asked ChatGPT to list the relationships in each show.

And at first glance? It looked pretty accurate.

But when I actually checked it properly, I noticed the problem: it didn’t just miss relationships but it invented some. Like, fully fabricated couples that never happened. Which is exactly the kind of thing that will quietly poison your analysis if you don’t have domain knowledge.

So I went back and manually reviewed each show’s couples with help from my colleagues who actually know the shows and that’s what made it possible. It worked, but it was tedious.

In the end, we labelled every couple with a relationship status: married, dating, broken up, divorced, secret, or kissed.

From there, it was “just” a matter of stitching everything together so each couple had the full profile: both personalities, both heights, hair colour, eye colour to be all in one place. Then I could start feature engineering basically turning raw attributes into signals the model can actually use.

So instead of feeding the model two separate personalities, I created (are they identical?) and how different are they: like introvert vs extrovert, S vs N, and so on).

For physical traits, I added height_diff_cm, because a raw height doesn’t say much, but the difference might. And for appearance I created same_eye_colour and same_hair_colour as simple binary flags because it’s an easy way to test whether superficial similarity appears up in the patterns.

It’s not about believing these features explain love but it’s about seeing what the data thinks it can explain.

I also found a dataset that maps the pairings into simple relationship categories: best, average, worst, or one-sided.

So for each couple, I check compatibility in both directions(A with B, and B with A) and then combine that into one label. If both sides are “best”, it’s best. If either side is “worst”, it’s worse. And if it only looks good from one side, it becomes one-sided.

That gave me one clean feature mbti_match_type_mutual that turns two types into something my model can actually learn from.

MBTI Relationship Compatibility chart

Here’s what I did next:

I turned all those messy relationship labels into a single numeric target so I could keep the modeling step simple.

First, I mapped each relationship status to a score. Married gets the highest score, dating is strong, broken up is low, and “secret” is negative because that usually isn’t a healthy sign. Then I did the same for personality compatibility: best match gets the most points, worst match gets negative points, and one-sided sits in the middle.

After that, I just add them together:

relationship_score_total = relationship_score + mbti_score

That combined score becomes my target:

target = "relationship_score_total"

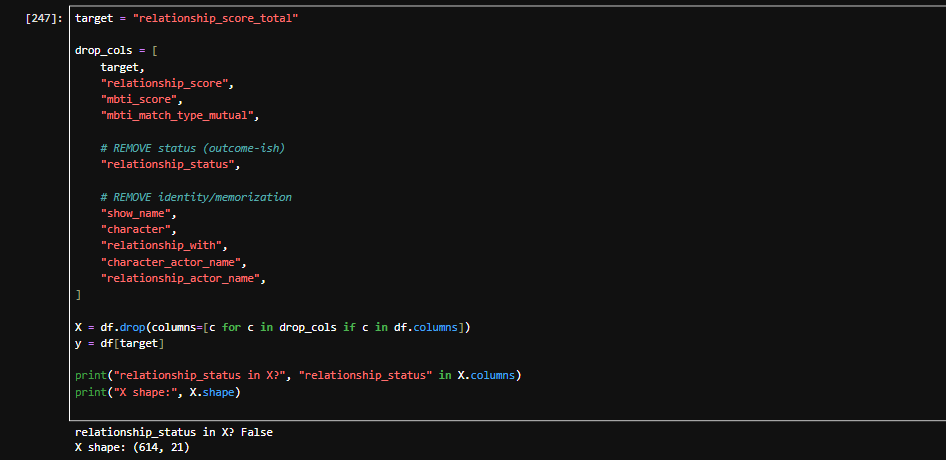

Now, the really important part: when I trained the model, I tried to be really strict about leakage from the start. I removed the target, removed the columns used to build it (relationship_score, mbti_score, mbti_match_type_mutual), and dropped identity fields like show name and character names so the model couldn’t just memorise couples. At the time, I genuinely thought I’d removed all the ways the model could “cheat”. I'll come to this realisation later.

In the meantime, I kept the model simple: a basic linear regression is a sanity check. If a simple model gets “too good to be true” results, it usually means there’s still leakage. And if it struggles, that tells me the problem is genuinely hard and the data might be noisy.

So I built a clean pipeline:

split into train/test

impute missing numbers with the median

impute missing categories with the most common value

one-hot encode categorical columns

train linear regression

evaluate with MAE, RMSE, and R²

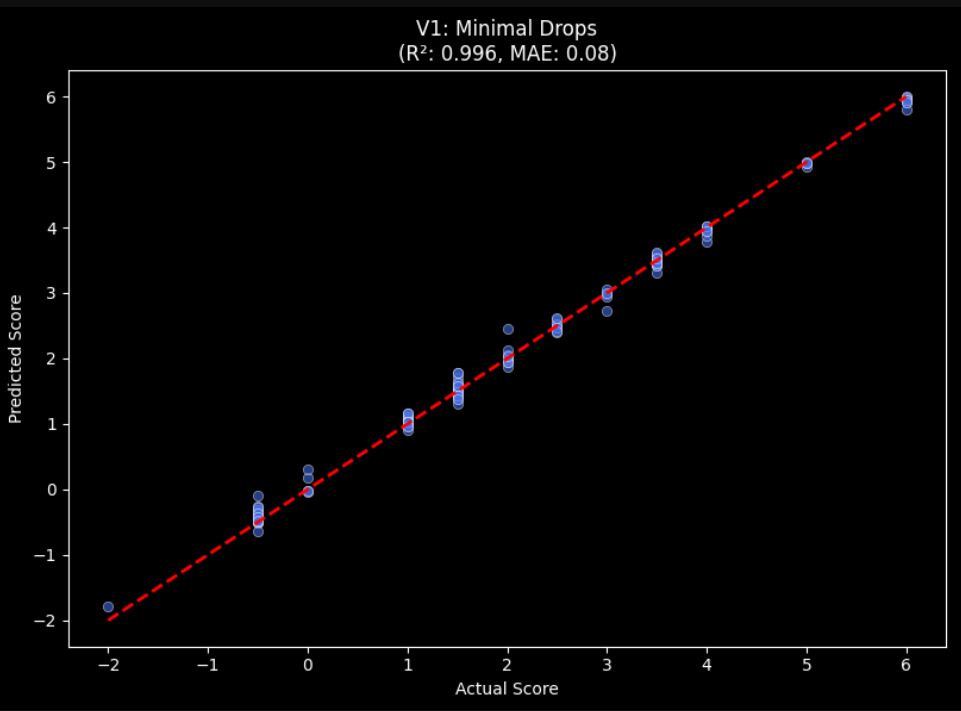

And honestly the results looked shockingly good:

Mean Absolute Error: 0.345

Root Mean Square Error: 0.496

R²: 0.926

Linear regression predicting combined relationship compatibility score (R² = 0.926) after strict feature removal and leakage controls

On paper, that’s incredible and I felt like, “I’ve cracked love” levels of incredible. Which is exactly why I got suspicious.

And this is where the “too good to be true” moment hit.

At first, I dropped the obvious leakage columns, the Myers-Briggs score I created, and the compatibility label I used to generate it. But I still had one massive cheat sitting inside the features: relationship_status.

Because think about it… relationship status is basically the outcome. If the model can see “married” or “broken up”, it doesn’t need to learn anything about compatibility, it’s already staring at the answer.

So I reran the whole thing properly and removed:

relationship_status

plus all identity fields like show name, character names, actor names

Same target, same split, same pipeline… just without the shortcuts.

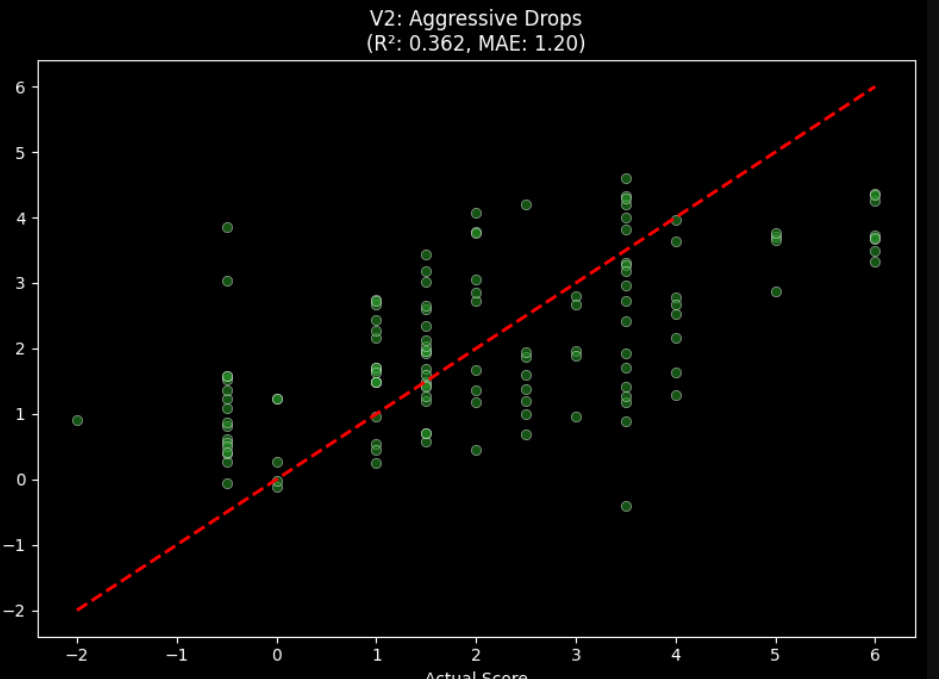

And the performance fell off a cliff:

Mean Absolute Error: 1.198

Root Mean Square Error: 1.456

R²: 0.362

Which is way more realistic.

Model performance after removing relationship_status and identity leakage — R² drops from 0.926 to 0.362

And honestly, this is the real story of the project: the first model wasn’t “predicting love” and it was predicting information I accidentally let it see. Once I removed the leaks, the model was forced to rely on actual features like MBTI distance, height difference, hair/eye flags… and suddenly the problem became hard again.

And that’s the real win: domain knowledge beats fancy models. The hard part wasn’t training linear regression and it was knowing what not to include, what would make the model “cheat,” and what features could exist before the outcome. The fanbase gave me MBTI labels, but the real work was turning that into usable signals.

That mindset doesn’t stop at romance datasets and it’s the same skill you need in business problems too. Take customer churn: one side of the relationship is the company, but the other side is a human which is messy, emotional, and ultimately the one deciding to leave. If we understand how people “break up,” we can stop treating churn like a random error and start treating it like a predictable pattern. That’s something I’d swipe right on.

We’re launching a closed beta next month so click here to sign up.

For more of this, come on the journey with us and keep being Evil