Is Die Hard A Christmas Movie?

You’ve heard this argument a million times. Some people are like, “It’s set at Christmas, there are carols, of course it’s a Christmas movie.” Other people: “It’s just an action film with tinsel, calm down.” So instead of screaming on the internet for the rest of my life, I did the only sensible thing: I built a model.

In this video I’m going to show you how I trained a simple Christmas-movie classifier using soundtrack data and basic movie metadata, and then used it to settle the age-old internet debate so we never have to talk about it again. We’re literally going to turn the Die Hard argument into machine learning.

So, what was the actual goal here? I wasn’t trying to build the biggest, fanciest AI in the world. The question was much pettier than that: can I take the stuff people always bring up in the Die Hard argument and turn it into numbers, train a model on a bunch of movies, and ask it, “Okay, based on everything you’ve seen… what do you think about Die Hard?”

To do that, I first needed a dataset.

I started with a dataset from Kaggle that listed Christmas movies from IMDb. It already had a good chunk of the information I care about: genre, director, IMDb rating, runtime, release year, and the type of title. Since this whole thing is about Christmas movies, it was pretty fair to say I could label those as is_xmas = True. And this is where it gets fun: according to that dataset, three films that data science is quietly treating as Christmas movies are Die Hard, Shazam!, and Batman Returns whether you agree with that or not.

Kaggle Dataset

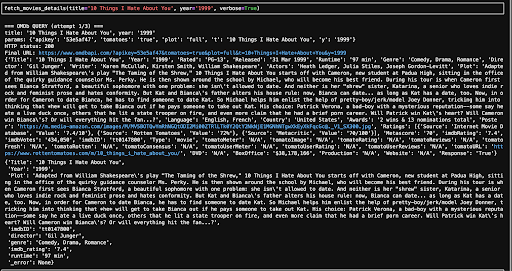

Since the whole point is to analyse why something is a Christmas movie, I also needed the full plot, not just a title and a genre tag. Luckily, from a previous Halloween video, I already knew I could use the OMDb API to pull detailed plot summaries. So I reused that pipeline here to enrich the dataset with a full plot.

Full Plot Dataset

The soundtrack search begins…

On top of that, for training the classifier, I also need non-Christmas examples, so the model can learn the difference. Those come from outside the Kaggle Xmas list, and I label those as is_xmas = False.

But that got me thinking: what else actually makes a Christmas movie sound like Christmas? And that’s where the idea of using music came in.

So I went off to hunt for soundtrack data like Santa doing his rounds with Google Maps on 1% battery. You’d think it would be easy to get all the songs used in these films but nope. The first problem was simply: where do I even find this? And if I do find a soundtrack dataset, will it actually cover all the movies I care about?

This is the side of data science you never see in the montage. It’s less “cool graphs and models” and it’s more crawling around the internet trying to find the right data in the first place.

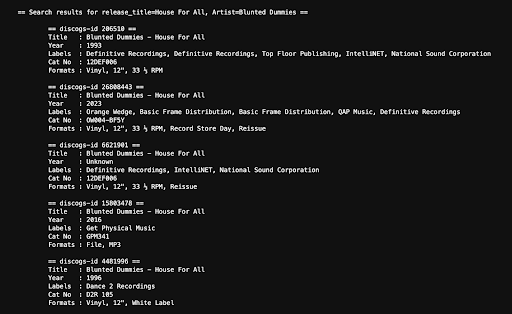

That’s when I stumbled onto Discogs. It’s an online database and marketplace for collectors, but for me it was a soundtrack goldmine. I could take a movie title, tack on “original motion picture soundtrack,” and suddenly I had a decent shot at finding the albums that do most of the heavy lifting for these films.

Discogs API

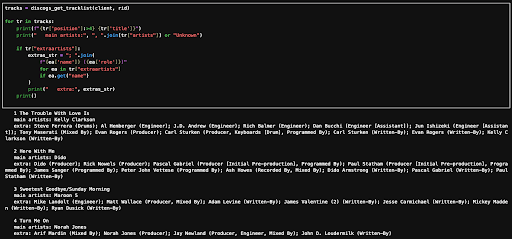

Discogs Tracklist

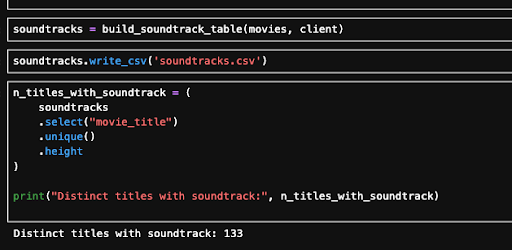

From there, I started pulling the tracklists for each movie so I could actually see the soundtracks but reality hit pretty fast. Out of 702 christmas movies, I only managed to find soundtracks for 133. Not great. At that point I knew I needed another plan, because the music side felt too important to just shrug and move on

Finding 133 distinct titles with soundtracks

That’s when I found WhatSong. No API, of course, and because I didn’t want to be the Grinch who ruined Christmas, I had to scrape it the old-fashioned way. But it worked: I ended up with soundtracks for 267 Christmas movies. I was genuinely happy with that and decided to drop the rest, since most of the missing ones were obscure titles that would just add noise to the dataset.

scrape and you’ll find 134 more!

What Does “Christmas” Mean to a Model?

For the non-Christmas movies things were much easier, well-known films tend to have their soundtracks well documented. After a frankly silly amount of wrangling and cleaning, I finished with 996 movies that had usable soundtrack data.

Remember, all of this is just to answer one question: what does the model say about Die Hard?

Before we can train anything, though, we have to answer a slightly cursed question: what does “Christmas” even mean… numerically? You can’t just write “vibes” in a spreadsheet. So I turned three big intuition buckets into features: the soundtrack, the text of the plot, and the people behind the film.

First up: the soundtrack. But before I could even count “Christmas songs,” I had to decide what counts as Christmas in the first place. I ended up raiding a PDF of Christmas vocabulary for kids and turning it into a big list of festive terms, because at some point I realised I was spending my adult life systematically defining Christmas and started to feel a bit like the Grinch.

Once I had that list, I could finally get practical: for each movie, I looked at the soundtrack and counted how many tracks were clearly Christmas-themed. That became a feature called n_xmas_tracks. If a movie has zero Christmas songs, it might still be a Christmas movie… but if it has twelve carols, that’s kind of a giveaway.

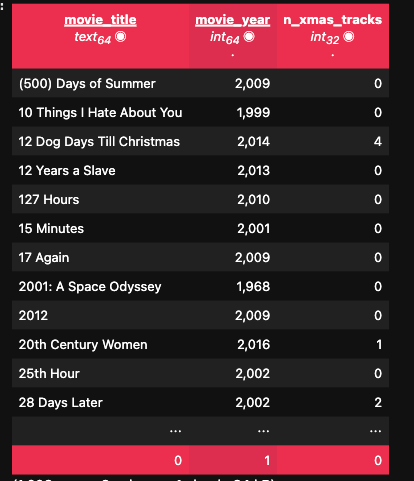

a DataSet of movie titles, the year they came out and the number of xmas songs

Because raw counts can get a bit wild…

I also created a log-transformed version, n_xmas_tracks_log. The idea is that going from zero to one Christmas track is a big jump, but going from eleven to twelve is not as huge a difference. The log transform basically tells the model, “Chill, yes, this film is very Christmassy, you don’t have to keep ramping the score up forever.”

Next, I turned to the plot. Using that festive vocabulary list, I ran through each movie’s synopsis and description and counted how many seasonal terms showed up. That gave me a feature called xmas_keyword_count basically, how hard the script leans into the holiday theme.

If your synopsis says “On Christmas Eve, an off-duty cop crashes a corporate Xmas party in LA,” that count goes up. If it just says “A man has a bad day in a tower block,” the count stays low. So now the model gets a rough sense of how much the story is literally talking about Christmas things, rather than just snow or “family.”

Then I looked at the people behind the movie, starting with the director. Some directors basically live inside Advent calendars; others have never touched a festive film in their lives. So I used the labels in my dataset to calculate how many Christmas movies each director has made. That became director_xmas_count. I also made a clipped version, director_xmas_count_clipped, which caps the value so one extremely festive director doesn’t completely dominate the model. If a director already has a few Christmas movies under their belt, their new cosy, snow-covered family film is more likely to be Christmas-y than, say, an action director randomly trying something with fairy lights.

Showing the Director and how many xmas films they are linked to

How the Classifier Actually Works

On top of that I had more boring features like runtime and rating. Not every movie has a runtime or IMDb rating filled in, so I created runtime_filled and imdb_rating_filled using sensible defaults where data was missing, just so the model doesn’t fall over every time IMDb drops the ball. These aren’t the star of the show, but they do turn out to have a small effect, which we’ll see later.

So that’s the feature engineering: soundtrack, text, director history, plus runtime and rating, all turned into numbers. Now, how did I model it?

I kept the modelling side deliberately basic, because the question itself is pretty simple: is Die Hard a holiday film or not? So I went with a logistic regression. It takes all those features as inputs, learns a weight for each one, and then spits out a probability that is_xmas equals 1.

If that probability is above 0.5, we treat it as “yep, this belongs in the festive pile.” If it’s below, it goes in the non-festive pile. No deep learning, no giant black box just a straightforward, interpretable model.

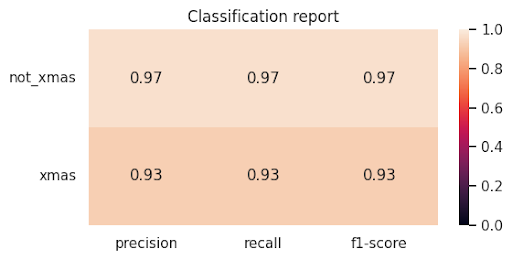

On the test set still with Die Hard held out the model does pretty well. It got about ninety-six percent accuracy overall. For the non-Christmas movies, precision was around 0.97 and recall was around 0.97, which means it very rarely calls a normal film “Christmas” by mistake.

For the Christmas movies, precision and recall were both around 0.93, so it catches most of the genuinely festive ones and doesn’t hallucinate too many. In normal human language: out of a hundred movies, it gets about ninety-three right. That’s decent enough that we can take its opinion seriously, at least as a party trick.

Classification report is it xmassy or not?

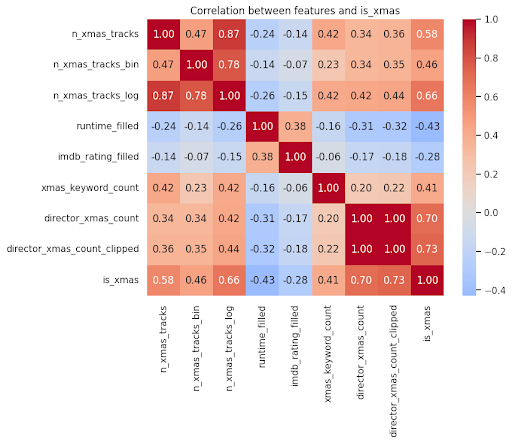

The nice thing about logistic regression is you can actually peek under the hood and see what the model thinks is important. When I look at the coefficients, the strongest positive signals come from director_xmas_count_clipped and director_xmas_count, meaning that if a director has a track record with festive films, their new one is much more likely to be flagged as such.

Chart on the correlation between features and Xmas

Right behind that are n_xmas_tracks_log and n_xmas_tracks: more seasonal songs in the soundtrack, stronger holiday score. xmas_keyword_count is also positive, which fits the intuition that if the plot is full of Santa, elves, and Christmas Eve references, the model leans towards “yep, this lives in the winter-holiday bucket.”

There are also a couple of interesting negative coefficients. In this dataset, higher imdb_rating_filled actually nudges the probability down a bit, and longer runtime_filled does too. That doesn’t mean “good films can’t be festive,” before anyone starts throwing snowballs in the comments.

It’s a Wonderful Life is not only a classic holiday film, it’s also ranked as one of the greatest movies of all time on IMDb. All this really says is that, in this particular collection, the holiday titles skew a bit shorter and a bit less critically adored than the average. Correlation, not cinema law.

image from the film It’s A Wonderful Life

The Moment of Truth: Die Hard Goes In

So, that’s the model trained, and we understand roughly how it’s making decisions. Now it’s time for the fun bit: we feed in Die Hard.

Think about what Die Hard looks like through the lens of these features. It is set at a Christmas party, which helps the text side slightly. There are some Christmas songs, but it’s not just a carol playlist from start to finish, so n_xmas_tracks isn’t huge. The plot mentions a Christmas party and Christmas Eve, but there’s also a lot of talk about terrorists, hostages, cops, and a tower block, so xmas_keyword_count isn’t going to look like Elf. The director is not primarily known for Christmas films, at least not in this dataset, so the director_xmas_count features don’t give it a huge boost. Runtime and rating are more like “serious action film” than “short cosy family movie.”

We take all those numbers, push them through the model, and out comes a probability. In my run, the model gave Die Hard a probability somewhere around seventy-something percent of being a Christmas movie. Not ninety-nine percent “obviously festive,” but also not a coin flip. According to this particular model, trained on this particular dataset and these features, Die Hard is a Christmas movie.

Does that settle the argument forever? Absolutely not. This model is still built on my labels for what counts as a Christmas movie in the first place, so my bias is baked in at the start. The features I chose reflect what I personally think matters: music, plot, director history. If you think “Christmas is purely about the story theme and not the date,” you’d engineer different features. If you think “any film watched on Christmas is a Christmas movie,” then… I can’t help you.

What I like about this, though, is that it turns a very emotional, fuzzy argument into something we can at least interrogate. Instead of yelling “It’s obviously a Christmas movie!” or “It’s obviously not!” we can say, “Okay, if we define Christmas-ness as this combination of soundtrack, text, and director behaviour, and we train on a bunch of labelled films, Die Hard comes out about seventy-odd percent Christmas.” You can disagree with the answer, but now you can point at exactly which assumptions you don’t like: maybe you think the soundtrack should matter more, or runtime should matter less, or director history shouldn’t matter at all.

Yippee Ki-yay mother*******!

If I wanted to push this further, I could swap out the simple keyword count for a proper text model that reads the full plot. I could get more detailed soundtrack data and look at exactly which songs are used. I could expand the dataset to include way more films, and maybe break it down into sub-genres like “Christmas romance” versus “Christmas action.” But honestly, for a first pass that exists purely to annoy people at parties, this is already plenty.

Do you agree with the model? If not, which feature is getting wrong? Let us know by joining our discord or subscribing to our youtube channel if you’re Team Christmas Movie, Team Action Film, or Team Please Stop Asking Me This Every December. And if you like this kind of “data science used for deeply unserious problems,” hit like, subscribe, and tell me what stupid cultural argument I should model next.

For more of this, come on the journey with us and keep being Evil