I Saved The Simpsons’ Christmas Using the Traveling Salesman Problem

Santa is out of time. He's got 32 houses to hit in Springfield, a tight schedule as it is, and he's spent so long optimising his naughty list, he hasn't got a single minute left to calculate the best route. But never fear, not even we’re Evil enough to not help Santa.

We’re going to use the Traveling Salesman problem to save the Simpsons’ Christmas before it becomes… MATHEMATICALLY IMPOSSIBLE.

Today we’re taking a look at three algorithms to save the magic of Christmas. Can any of them do it? Let’s find out.

So there comes a time in every adult’s life where an annoying child asks how Santa could possibly visit every house out there. I’ve no idea why we don’t get given response scripts on our eighteenth birthday, but today I’m going to give you what you need to baffle the child so much that they never ask the question again. Bells ready to jingle? Here we go.

The Traveling Salesman Problem Explained: How Santa Finds the Perfect Route

So my starting point is the map of Springfield where I have painstakingly plotted the houses, or places of work, let’s be real the Simpsons hasn’t exactly shown us where Dr. Nick resides on this map. The whole process of getting this to be something readable was a nightmare.

However, I originally made this map to send Bart Simpson Trick or Treating using a combination of Dijkstra’s and Orienteering Algorithms so today I get to skip all the set up and take you into the good stuff: how do we use the traveling salesman problem so that Santa completes his hit list?

So if you’re not already familiar with the traveling salesman problem, it’s a route finding problem from the world of computer science that has the condition that the traveling salesman, in this case Santa, must start at one location, visit every other location and then return to the starting point. Let's just say Santa can only travel between towns at specific points and that's why he has to return to the same starting point. It just makes the maths easier and avoids a long, complicated detour.

It’s not strictly the case that Santa must visit each location only once, especially in the case of big graphs where every node doesn’t necessarily connect to every other node, but the way we mapped Springfield means that he has a direct path between each and every character so the optimised path for us will be to visit every single member of Springfield exactly once.

Except Moe, by the way. He was broken for my Trick or Treating video… I was going to fix him for this video but… turns out he’s on Santa’s naughty list anyway so I don’t have to!

There are many ways to solve the Traveling Salesman problem with a variety of different algorithms but today we’re going to take a look at three and make a recommendation that will save the Simpson’s Christmas!

Hopefully getting Santa around Springfield is a lot less chaotic than Homer’s makeshift sleigh

Why O(n!) Hurts

So when solving any technical problem, sometimes people make the mistake of instantly jumping to the most complicated algorithm, but actually in the real world simplicity wins for a few reasons: it’s easier to implement, it breaks less and when you do get a bug, it’s much easier to diagnose and fix quickly. And I can tell you first hand from a decade in quant and data science departments that being able to fix it quickly when the proverbial hits the fan is one of the most important gifts you could give yourself.

So with that in mind, we’re going to start looking at this problem by taking the most straightforward approach: The Brute Force Method. Let’s pick a starting point, Kent Brockman’s house, picked at random because I already calculated it for a later Art Attack moment.

The most basic thing we can do is check every single path. Kent Brockman to Ned Flanders. Kent Brockman to The Simpsons. Kent Brockman to Mr Burns. There are 30 different places that he can go from there so we have 30 options for our first step.

Say we pick Ned Flanders. We’ve already been to Kent Brockman so we need to go somewhere new. We have 29 options and whichever one we pick has 28 paths from there.

As I’m building this up you can start to see why this problem is so hard. If there are 30 ways we can go from the first node to the second, and 29 ways we can go from the second to the third, that’s already 870 different paths and we’ve moved literally two nodes. Following that through we get 30 factorial number of possible paths which is a number that looks like this: 265,252,859,812,191,058,636,308,480,000,000. Good luck trying to read that out loud.

To give you an idea of how big that is the number of seconds in a million years is in the range of ten to the power of 13. Put it this way, if I set this off running, the universe would end before my code did. Provided it didn’t crash first.

One of my favourite things about data science is that we come from often relatively theoretical maths, stats or similar backgrounds and not coding so when the computer scientists tell us it’s an O(n!) problem we just nod along like we know what they’re talking about. But I’m breaking the taboo here and telling you that I took one for the team and looked it up for this:

It literally means that the number of operations is some constant times n-factorial. So as n grows, the number of operations increases in line with n factorial. And that’s exactly what we have here; a brute force methodology so computationally intensive that you’re blowing your memory or the universe itself.

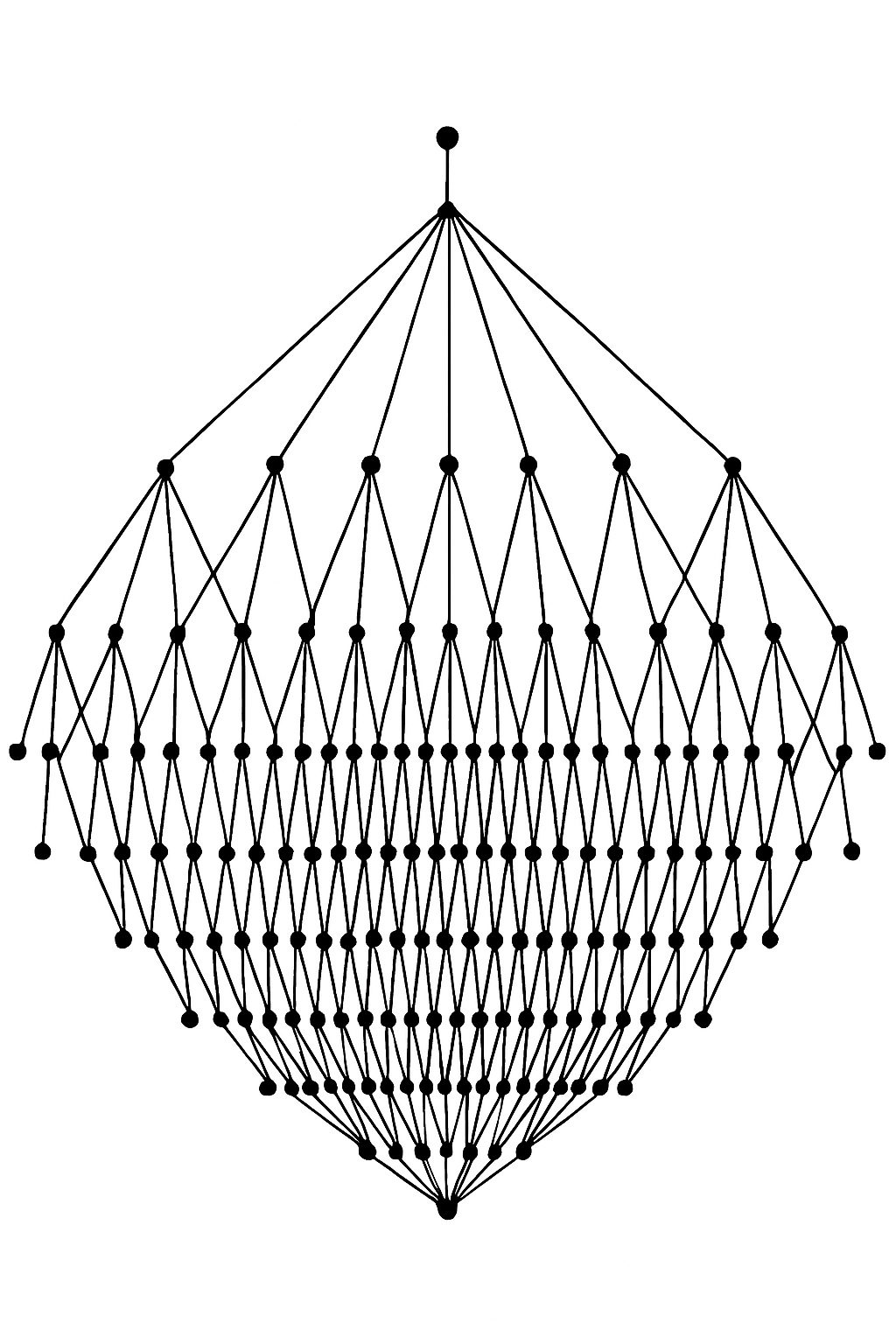

branching decision tree explosion diagram

Working Smarter, Not Harder

Alright so brute force will give us the best possible path but the time it takes isn’t really going to cut it here and in the real world that often means we need to make optimisations. So let’s start by seeing if we can improve on this algorithm.

The biggest problem with Brute Force is the sheer number of paths we need to calculate in order to find the best possible one, so we’re going to look for a way to cut down the number of paths we have to evaluate to reduce the computation time significantly.

One thing we can do is something called the Held-Karp algorithm which makes use of dynamic programming techniques such as recursion. A topic for another video but I’m going to give you the high level of how it works now.

The key idea is that we solve the huge problem by breaking it down into smaller, related subproblems. For example, the overall problem is: Find the shortest path that starts at Kent Brockman, visits all 31 houses, and returns.

We can break that down to: What is the shortest path from Kent Brockman to any final house, having visited a specific, known subset of all the other houses? Then we can tag on the jump from that final house to Kent Brockman at the end. Really it’s the exact same problem, we just stop one house earlier.

Let’s go down a few layers until we reach somewhere where the numbers are manageable. Let’s go to level four: Say we want to find the shortest route from Kent Brockman to Mr. Burns, passing through a specific set of three houses along the way. Once we find that shortest distance, we store it.

Now, when we move up to higher layers we never have to calculate the shortest distance between Kent Brockman and Mr Burns passing through three houses again, we can immediately reuse that stored shortest distance. We never have to recalculate the best way to get to those first four stops again.

Because we’re not having to calculate the distance for every possible path starting at Kent Brockman and travelling to Mr Burns after three houses, we actually cut down the computational time significantly. This drops the complexity from the ridiculous O(n!) of Brute Force to a much more manageable O(n^2 2^n) while still maintaining the rigor of knowing we are not overlooking the optimal path.

There’s only one problem, that’s still a huge amount of paths to take. I mean we’re slightly less than the number of seconds in a million years but… not by much. It’s time to go even deeper.

Smaller solved pieces build the full answer

Trading Accuracy for Speed: The Greedy Algorithm

The reality of the traveling salesman problem is that you don’t really have to have many nodes for it to become computationally impossible to get an accurate solution. I’ve not even bothered to try and plot locations for most of the kids of Springfield (Nelson, Martin, Sherri and Terri, Fall Out Boy and already we have a problem that’s just far to complex to solve. So like much of life, if we want to get things done, we have to make compromises.

One such algorithm that tips the balance much closer to speed at the sacrifice of some accuracy is the Mr Burns- I mean the greedy algorithm.

It’s so called, I guess, because it’s the opposite of delayed gratification. It’s the hedonistic pursuit of the best path right in front of you with no regard to the price you might have to pay in the future.

The implementation is actually really straightforward: after Santa visits a house, he chooses the nearest house that hasn’t been visited to go through next.

It’s the definition of short term gain for long term pain as taking the shortest route from your current location means doubling back, maybe more than once and maybe across great distances.

But the time savings gained from this approach are pretty hard to beat and Santa’s left it pretty late in the year to start planning his route so sometimes we allow a bit of extra travel if it means presents get delivered on time. The reindeer only get out once a year anyway.

To show you just how much the greedy algorithm speeds things up, I actually ran these algorithms myself, albeit on a subset of nodes - I don’t have multi millions of years worth of seconds to wait.

I was playing around with different numbers of nodes to find good candidates for the video and when I ran with eleven nodes it took 58 seconds to wander round the streets of Springfield. When I upped that to twelve, it took 696. Eleven and a half minutes. I didn’t dare run for thirteen nodes, it’s an unlucky number anyway.

I then ran Held Karp which decimated the times to 0.2 and 0.7 seconds respectively for eleven and twelve nodes. That’s a huge improvement but that’s only because we’re running for just twelve. The problem gets increasingly bigger the more nodes we include.

And get this: For the greedy algorithm I got to take the hedonistic route myself. Instead of implementing it, I took the path of least resistance and used the approximation built into the graph library I was using. Quick to code and even quicker to run, we’re very much in millisecond territory here. In fact, so much so that I ran for the full 32 node graph in 0.03 seconds. Speedy, right?

However, what we save in time we spend in accuracy. While both Brute Force and Held Karp agreed on the shortest route for the eleven and twelve node graphs, the distance of the greedy algorithm was 1584 compared to the more accurate 1486.

The twelfth node saw the addition of Mr Burns - I really think I need to do some deep reflection about why I use him for every example - and fittingly the difference in cost was much more significant. A distance of 2715 compared to the maximum accuracy of 2303.

Mr Burns is the epitome of Greedy!

What Data Science Is Really About

So I guess what we’ve learned from this is that sometimes we need to compromise. Sometimes we don’t get to have our cake and eat it, and we have to concede on certain points (the accuracy) to get what we really want (Santa to be able to deliver presents on time). Who said nerds don’t have social skills?

And also, I actually wanted to use this series to showcase just how broad data science is. Ultimately, what I’ve explained today all sits firmly in the domain of computer science, but data science requires us to be versatile, to pull from many tools in our toolkit to find the best solution to whatever weird problem our boss has dreamed up next. Oh wait… that’s me now!

I joke but at Evil Works we’re living and breathing data science after careers of doing this for real and that’s why we’re on a mission to improve the experience of data scientists by creating a platform to take your workflow from Held-Karp to Greedy, but without the loss in accuracy.

We’ll be having a closed beta for our subscribers to try it out early next year, so if you’re interested in finding more, get yourself on the waitlist in the description. I’ll happily info dump to anyone who’s keen.

Otherwise, like and subscribe to our youtube channel and tell me, what’s the most hedonistic hack you’ve managed to pull off in your data science projects.

Come on the journey with us and keep being Evil